After a glorious day off, where I mostly read books and used a petrol strimmer to utterly destroy a number of stinging nettles, I returned to the lovely Oak Hill College for the start of week two…

Anaesthetics

Our first talk today was from Hilary Edgcombe, who started with photos of an elephant and a boa constrictor under anaesthetic, which was cool.

Anaesthesia is the absense of sensation: so this includes local and general anaesthesia.

General perspective on world anaesthesia:

- Good anaesthesia is

- Safe

- Comfortable for the paatient

- Comfortable for the surgeon

- Preferably simple, economical and fast

11% of world’s disability-adjusted life years are lost due to conditions amenable to surgery. Safe anaesthesia is necessary for surgical care.

Safe anaesthesia is not available worldwide:

- In the UK, anaesthesia related mortality is 1 per 185000

- Malawi central hospital: 1 per 504

- Togo teaching hospital 1 per 133

- South Africa: 1 in 4 maternal deaths anaesthesia related: 90% avoidable

Key causes of anaesthesia related mortality:

- Airway failure

- Aspiration (getting stuff in the lungs, leading to pneumonia or pneumonitis).

- Hypotension

- Regional anaesthesia failur (high spinal)

Of 41 anaesthetic clinical officers in Malawi, 5 had seen a failed intubation. 2 had seen a case of pulmonary aspiration. 9 had seen a case of high spinal (requiring intubation)… in the preceding week!

A lot of this is due to lack of equipment – in one study in Uganda, only 23% hospitals had enough equipment to safely anaesthetise an adult, 12% enough to manage a child and 6% enough to do a C-section.

Golden rules for Anaesthesia

- Pre-assess your patient: to optimise their condition, to make a sensible plan, explain/allay fears/concerns.

- Know your equipment.

- Work out what you expect to happen when:

your anaesthetic,

encounters your patient,

with their surgical problem,

and their other comorbidities - Do a bit of catastrophising: formulate plan B, plan C.

- Monitor your patient: ideally HR, BP, pulse oximetry, and end tidal CO2. Worst case, make sure you are looking at and feeling the patient.

- Remember recovery.

- Don’t get into trouble you can’t get out of: if you think the airway will be difficult, don’t stop the patient breathing, etc.

Pulse Oximetry

Hilary then showed us a video about an exciting push to get pulse oximetry machines worldwide:

[iframe width=”640″ height=”360″ src=”http://www.youtube.com/embed/iKEJJGxZA3g”]

Oxygen sources and delivery

For the sick patient (who needs more oxygen or who can’t get it to their cells effectively), or for some anaesthetic techniques, oxygen is helpful. It can be difficult getting hold of O2 in the developing world for logistical reasons.

She shared a story of a patient who died due to the oxygen cylinders being full of NO2, and another of a paedriatic ward that had a 2,000 litre cylinder that they used with neonates with no pressure control, so the babies were practically being inflated by the force of gas…

Pipes:

- Lucky you!

Cylinders:

- Money – expensive

- Logistics

- Safety – have they been maintained?

- Safety – which gas?

- Safety – what pressure?

- Safety – traumatic injury?

- Duration

Concentrators:

- Need a power supply.

- Reliable if maintained and cost effective.

- WHO standard: operate up to 40 degrees, in 100% relative humidity with unstable mains voltage and dusty environments. Passing military shock, vibration and corrosion tests. Should be supplied with 2 years of spare parts.

- Can supply 90-95% oxygen.

Ketamine

Ketamine is a super drug, its a hypnotic, analgesic, amnesic. It is not a muscle relaxant. It has some weird effects, since it can lead to patients have their eyes open throughout, and causes emergence delirium (the reason we don’t use it in UK).

Other key points, some positive, some negative:

- Tend not to end up hypotensive – slight rise in BP, HR and RR.

- Patients tend to maintain their own airways.

- Probably the least dangerous anaesthetic to use.

- Can cause laryngospasm due to hypersalivation, but less commonly than thiopentone.

- Can cross the placenta, giving you a spaced out baby.

Key Ketamine Safety Points

- Hypersalivation may be minimised with premed atropine 20mcg/kg

- On take excitement and post-op delirium may be minimised with benzodiazepine co-medication

- Remember ketamine can cause apnoea if giving fast IV.

- Avoid in patients with closed head injury, penetrating eye injury, and in whome cardiovascular stimulation would be harmful.

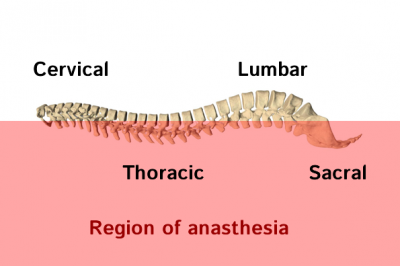

An introduction to spinal anaesthesia.

A local anaesthetic block of all the nerve exiting the spinal cord below a particular level. Low risk – but not “no risk”.

A local anaesthetic block of all the nerve exiting the spinal cord below a particular level. Low risk – but not “no risk”.

In an adult, the spinal cord ends around L1/L2, so going in below that, you are unlikely to hit the spinal cord.

There are two types of any spinal drug. Normal, and heavy – the normal types are roughly the same weight as CSF. The heavy types are mixed with glucose, and obey gravity going low. However, due to the lumber lordosis, if you give someone a heavy drug and lay them down immediately, the agent can pool in the thoracic region – see diagram on right.

Common local anaesthetics: lidocaine, bupivacaine, tetracaine. Need to know relative baricity and appropriate doses for the drug. Exclude preservatives: since they can cause neurotoxicity.

In the West, we tend to give some opiates with the spinal, but this is not something generally done in the developing world.

Problems with Spinals:

Immediate

- Block doesn’t work.

- High spinal (cardiovascular compromise)

- Very high spinal (cardiovascular & respiratory compromise)

- Total spinal (cardiovascular, respiratory and CNS compromise)

Early

- Headache

Late

- Haematoma

- Infection

- Ongoing nerve damage

Contraindications

- Inadequate facilities –

- Patient refusal

- Raised ICP

- Sepsis at site, or systemic sepsis.

- Abnormal clotting

- Anatomical deformity

You need:

- IV access and fluids

- Some sort of vasopressor and atropine

- Someone to monitor the patient

- Resuscitation equipment

- Position the patient well, and use aseptic technique

- To look for delayed hypotension

There is a free Developing Anaesthesia Textbook available at www.developinganaesthesia.org

Surgery for the non-surgeon

John Rennie and Colin Binks shared the next talks about surgical matters. They both apologised for the dwindling capacities of their ageing neurones, but assured us that with enough prompting they would be able to recall the more important arteries, etc.

John Rennie and Colin Binks shared the next talks about surgical matters. They both apologised for the dwindling capacities of their ageing neurones, but assured us that with enough prompting they would be able to recall the more important arteries, etc.

“You must take your bible, your toothbrush, your anti-malarials and the Textbook of Primary Surgery. It’s brilliant, full of pictures, and perfect for those of you who are far more comfortable cutting sausages than cranial burr holes”.

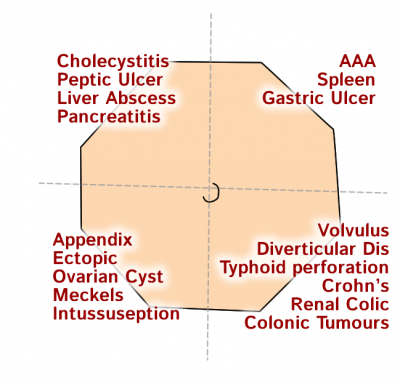

Acute abdomen

Does my patient need surgery NOW?

- Bleeding (immediately)

- Strangulated bowel (need to stabilise patient first).

- Peritonitis – perforation, pus (need to stabilise patient first).

Does my patient need surgery at some time?

- Think: what resuscitation or other treatment is needed whilst observing?

- Can I do the surgery?

- Action: Active observation/resuscitation/refer.

Does my patient definitely not need surgery?

- Respiratory problems – basal pneumonia

- Gut problems – gastroenteritis or ileus

- General illness – diabetes, viral infections, uraemia, sickle-cell crisis

- “Surgical” – cholelithiasis, pancreatitis

- Gynae – ovulation pain, salpingitis

- Nerve pain – herpes zoster

Fluid Resuscitation

- Clinical assessment: if a little dry, potentially 5% dehydration, with very shut down, sunken cheeks, 10%.

- Deficit (ml) = % dehydration x Wt (kg) x 10

- This is 7000 ml for 10% dehydration in 70 kg adult and 1000 ml in a 10 kg child.

- Use N-saline or Ringer’s lactate for deficit

- Resuscitation for fluid deficit will normally take 3-5 hours to optimise patient’s condition.

- Patients with active bleeding need surgery as soon as possible.

How to find a perforation in the developing world…

CT scan– unavailableBowel sounds– unreliableRebound tenderness– unreliable- Loss of liver dullness – a valuable, underused resource. Air in abdomen will reduce dullness on percussion.

In Uganda, there are currently 27 surgeons for 10 million people. Last year in Ethiopia, there was only one new surgical graduate in the whole country.

Differential for Acute Abdomen

How to Operate for Dummies (AKA Medics)

- Get a nice sharp knife.

- Cut through the midline.

- Go through the fat.

- Carefully cut through the rectus sheath.

- Cut through the peritoneum, hold it aside from some clips.

- There will be a big woosh of horrible contents, if there has been a perforation.

- If there is bowel contents in there, use some sterile water to wash it out. If you haven’t got that, tap water is an awful lot cleaner than what is already in there.

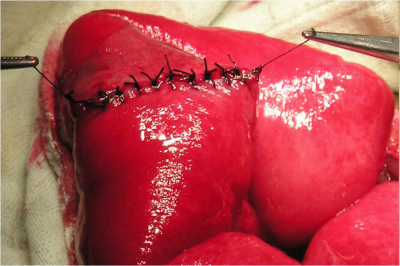

- Find the hole in the bowel.

- Gentle drag the omentum over the hole, and put some big loose stitches around it.

- Leave a drain in the abdomen, through a separate hole.

- Using some strong nylon, take all the layers together and close in a mass closure technique. If you have no strong thread, buy some fishing line and sterilise it.

- Put some loose sutures in the skin, closing it properly a few days later.

- Fill them with antibiotics.

“You can do good surgery without electricity, although it is rather nice to have a lightbulb…”

Popping in a chest drain

Use clinical signs to ascertain which side.

Use clinical signs to ascertain which side.- Use some local anaesthetic all the way through – which then tells you that you are in the right place.

- Wait several minutes

- 5th intercostal space, mid-axillary line.

- Go just above the rib – because the vessels hang underneath the ribs.

- Make a small cut with a scalpel, then push through a Spencer Wells (see right).

- You will go through skin, then fat, then pleural.

- Open the forceps, and pop your tube through the gap.

- There will be pus, fluid or air that comes out.

- Put the other end of the tube under a water seal.

- Keep the underwater seal lower than the patient.

Suprapubic catheter

- Needs a full bladder, dull on percussion.

- Find the point an inch or so above the pubic tubercle, in the midline.

- Pop in lots of local anaesthetic.

- Make a small vertical incision – just 2 inches high – but add another inch for each depth of fat in obese people.

- Dissect down through the fat to the lineo alba – a white line down the midline.

- Carefully slice this in half, then hold the two sides apart.

- If there is any gut in the way, push it aside.

- Make a very small cut, and pop a Foley Catheter through the wall of the bladder.

- Stitch it in place.

Ascitic tap

- Lay patient on side.

- Measure 5 or 6 inches from the midline laterally, avoiding rectus sheath.

- Pop it in.

Practical Sessions

After lunch, we had an afternoon of practical workshops with the team from this morning. My spinal actually worked!

Performing a spinal

We had a practice at both upright and lateral spinals on some models. Rarely, I didn’t hit spinous processes, and got loads of juice out, and popped some in! Good times…

Wound management

Wash out the joint, especially if there is debris in the wound.

Wash out the joint, especially if there is debris in the wound.- Deal with it within 6 hours, to prevent infection.

- Use anaesthesia.

- Examine blood supply, nerves, tendons, other structures.

- Bone chips should be removed from trauma wounds.

- Tendons and nerves should be tied end to end with silk stitches, and keep the wound moist.

- Give tetanus prophylaxis.

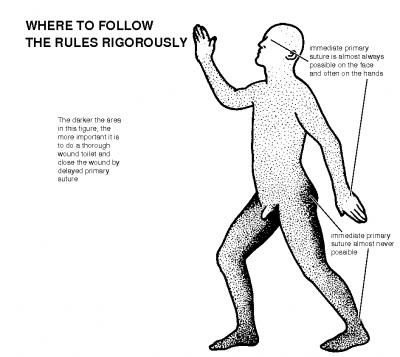

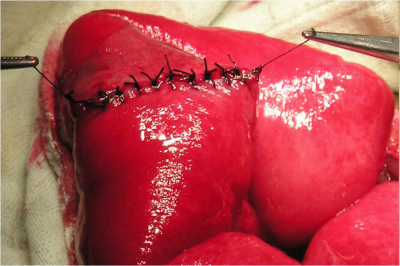

You would often not stitch the wound after you have debrided it, since you need to allow muck to escape. Different areas of the body will have different rules: click picture on right for more details.

- Primary Suture – immediate closing

- Delayed Primary Suture – delayed closing after 3-5 days.

- Secondary Closure – often for older wounds that have began to heal themselves through granulation, and may need skin grafting.

There was also a fantastic Dentistry Basics session, which involved pulling teeth from a pig, the use of peroxide gel teeth whitening and a Suturing Basics session. By the end of the day, I was definitely very ready for a curry. Which was lucky, since I was about to go to the East End for one.

Read about a day where I got to pull teeth from a pig… Day Seven: Surgery http://t.co/Fs18Rb21